A Death Observed, Part III | I am now Yours

The story of my diminishment by the fangs of the psychosomatic plague gripping our age (Part III)

And if I am to die before my time I consider that a gain. Who on earth, alive in the midst of so much grief as I, could fail to find his death a rich reward?

- Sophocles, Antigone (ca. 441 BC)If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.

- George Eliot, Middlemarch (AD 1871-2)

In the last days of Christmastide, while traveling in the rather languid days of the newborn AD 2023, I was, for a night, devoured by the tempests of a cytokine storm. Now, such storms are not inherently evil; they are, as it were, well-intended by the immune system. However, when the object of the storm is reflexive; when “immune” is prefixed by “auto”; then the storm’s good intentions do little else than pave that idiomatic road towards hell. And so it was with me. Injuries from a decade ago stabbed through with pain; heart rate reaching nearly 180bpm; cardiac inflammation, diaphragmatic cramping, pulmonary ache; my head, wreathed in roiling pain—and of course, only the right side of my head; the dull pounding of the ear crescendoing with the exploding heart rate; vomiting ceaselessly (painful when abdominal muscles are cramping), interspersed with choking on the aforementioned albumen sludge which was filling up my throat; an abdomen so swollen with inflammation that it was distended by about 4"; and the greatest suffering, prowling like a lion in the dark, but never achieving more than prowling. Much of this I have felt before, of course, from “ordinary” cytokine cascades, one of the body’s nuclear options against pathogenic attack (e.g. food poisoning can solicit many of these reactions). But the hemispheric wreath of pain about the head? The cardiac inflammation? The stabbing of old injuries? The flood of albumen sludge?

A long time ago, I was sitting in BIOL 101, listening to the professor talk about plant seeds. I don’t particularly remember much of what she said in that lecture, save her response to a student’s question. She had just finished describing an extracellular signaling cascade by which the various components of the seed communicated with one another that it was time to “plant,” to manufacture and shoot out roots and begin to, well, turn into a plant. And a girl asks the question: “But how does the seed know which way is down? So, like, the roots don’t grow sideways or up or whatever. How do the roots know how to grow down?”

The answer: “Oh, there are proteins that sense the gravitational direction.”

The follow-up: “Uh, how on Earth do they do that?”

The candid last word: “Yeah, so, we don’t really know.”

A thought experiment: the human form, the image of God, which is the form of Christ, Logos made Flesh—human physiology, and, even for argument’s sake, just only a sliver thereof, the immune system: might it be more, or less, complex, than a bean?

Years ago, Penelope worked in an Ivy League research lab. Years before that, we studied organic chemistry together in undergrad. She is no stranger to literature, either research or clinical (much less the English and American fictional varieties). And so what Penelope did, in the face of the encroaching blackness of the blood, was make the rather reasonable judgment that that which was demonstrably clinically efficacious in India, all across the continent of Africa, and most of South America—to say nothing of its scattered use in the United States—was worth a shot in my exotic case. With no firm diagnosis to go off of—my symptom cluster was as yet totally absent from any and all literature either of us had found—it was a blind leap: she asked me to work up dosage parameters, and she overnighted me a volume of Ivermectin (IVM) to match those parameters. Neither of us particularly believed that I had a WT SARS2 infection; the symptoms were all wrong. After all, the symptom clusters of SARS2 were well established by that time. And my plight was, after all, according to medical literature, utterly novel. But, for the explosion of such novel symptoms to intersect, coincidentally, by sheer dumb luck, in lackadaisical happenstance, with an epoch entirely revolving around a novel infection and, more specifically, the novel therapies therefor, was simply too much novelty to bear. Maybe not for a materialist, as most in the medical industrial complex are—but Christians are not meant to be materialists.

A few hours after what I recall was the second dose of IVM—so around twenty-six hours after I started—my midday Excedrin overdose was fading. The quite unpleasant sensation of my ear rhythmically squeezing up the sludge through the ear canal, not unlike regurgitation if it could be slowed down to taking minutes at a time, began its recapitulation. The pulsatile pain began to crescendo. The eyes seared—all was as “normal,” which is to say, as novel, as ever. I plucked myself from my perch atop the bed, from sitting up against the wall, and trundled to the kitchen table, steadying myself on every wall along the way. As I unscrewed the lid and began to upturn the Excedrin bottle into my hand, I froze, cocking my head with, as ever, befuddlement.

The pulsatile pain, the stabbing, the chef’s knife through the skull: it was gone. Not dampened, not moderated, not milder: just gone. In less than a minute, it had simply melted away. Yes, of course, much pain still persisted. But it was a very different pain. A dead pain, not a lively, sparkling, vivid pain. Just aching, punctuated by rare flailing stabbings. The tinnitus, too, had drifted into about mf from what had squarely been ff. The eyes, while still sliding in and out of focus, were only sore now—not searing.

The next day, the blackness in the blood was gone. The sludge continued out of my ear, but no longer with the grotesque squeezing motion of the ear canal. It was draining, now; it was no longer extruding. Within a day or two, I could lay my head down. I could lie down. When I would sleep, the ear would drain, indelibly staining whatever it touched. But eventually, it too stopped. The greatest suffering began, ever so very, very slowly, to dissipate. The hearing loss—for, amidst the tinnitus, my right ear had also all but lost all sense of hearing (I could snap my fingers an inch from my ear and hear nothing)—too began to, very slowly, dissipate.

Just after completing my course of IVM, so about ten days later, I did encounter and fall victim to what was putatively WT SARS2. And in my shattered state—beginning to heal, yes, but hardly healed—I persevered for several days before I accepted Penelope’s offer of yet more IVM. As before, after about 26h, the IVM took effect: and the coughing paroxysms, wretched inflammation, mildly damaged smell and taste, etc., all melted away within two or three days. And again, I was back to where I was the first time I found healing: a place of instantaneous acute relief, relief so astoundingly indiscriminate, so extravagant, so totalizing, that my befuddlement perhaps reached its apex in this time.

But, like an unfinished project which lingers in the basement a little too long, and soon is only languishing, the healing, well, faded from view. That which the IVM could, and did, halt, it could not undo. For whatever IVM’s powers are, anti-inflammatory and antagonistic towards SARS2 pathology though they be, tissue regeneration is not one of those powers. And I’ve read the glib factoids, much less the biology textbooks: “When you lose brain cells, they don’t come back”; “Hearing damage is permanent, because the cells are too fragile to be repaired”; “Nerve damage is often irreparable"; “Diminished eyesight simply does not return.”

Yes, that’s what “they” say, those delightfully generic, unnamed third-person plural entities around which so much of contemporary life revolves. “They” say an awful lot these days. And they said, in short, that my body—that I—was totaled. I undoubtedly felt that way, of course. But feelings, like our memories, are flighty at best. And so, despite what they had to say, I had a question: What if there were something, or someone, that could make death into a beginning? O, the materialists, they have a ready answer, of course; and they shall set it as the cornerstone of their estate in hell. Let them, well, go to hell, as it were. For they are there already, and already discontent with its cramped accommodations, and so they have set about building it upon the Earth.

The human body is a wonderful thing. The human body is a splendiferous thing. Splendiferous, splendi- + -ferous, I have to imagine, with the latter arising from the Latin: fero, ferre, tuli, latus - to bear, to carry. (Remarkable, the things that I unearth in this shattered mind.) The human body is a splendor-bearing thing. The human body is a wondrous thing. Full feeling returned to my face. Most hearing has, by this time, returned to my right ear. Its clarity and acuity remain damaged, and the tinnitus hums along at mp or so—rendering that ear largely useless in musical and conversational contexts—but it is several quantum leaps removed from where it was in January AD 2022. My eyesight is ever so slowly equilibrating, but it requires an enormous amount of blood sugar to function well. I could explain why, but I am content to simply remark that the human body is a wonderful thing. My shattered mind is, day by day, slowly being rebuilt. T.S. Eliot’s 1934 play The Rock comes to mind:

Where the bricks are fallen

We will build with new stone

Where the beams are rotten

We will build with new timbers

Where the word is unspoken

We will build with new speech

And so it is in my mind, cluttered with wreckage though it be. The debris of half-toppled suppositions is being carted away, the scattered, crumpled turrets of long-forgotten ideological foibles swept aside to clear the site for—well, for what, I know not. You would have to inquire with the Architect. Does the clay interrogate its Shaper? And it has been over a year, and progress on this front often seems scant, and I suppose I look like a fool much of the time. I start sentences, forgetting their ends; I end sentences, forgetting their starts. I begin jokes, forgetting their middles; and when God is feeling particularly comedic, all of these coincide with my mishearing what someone said in the first place. In a sweeping rhetorical flourish, the air dripping with a drama-charged pregnant pause, I might stop in the middle of a sentence: but my audience will likely be left expecting for some time. The pause is fallow. I am staring into a mental void, realizing that I have forgotten how grammar works and, more problematically, what I was even saying. To combat such tenuous cognition, I eventually ended up with two doses of caffeine daily, 100-250mg apiece. They each buy me a few hours of something resembling mental acuity. I like to call it cognitive redlining. As the name suggests, however, it is not sustainable for long periods of time. And besides, irrespective of caffeine levels, I sunset rather severely, making it difficult to hold my thoughts in order too long after dark without extraordinary exertion of willpower (blood sugar, basically). Intriguingly, the sunsetting is combated by dear old ethyl alcohol. The vive of alcohol helps to clear away the mists which settle over the mental wasteland come evening. Unfortunately, alcohol is rather inflammatory, and so I do not partake very often. When I can strike the balance, equilibrating the stimulants and the depressants, I am left feeling approximately “normal,” or what I think normal might be. For I do not really remember at this point what “normal” was, much less is. I do not remember much of what health feels like at all, actually.

In addition to the duet of caffeine and alcohol, my body, which is to say I, have had many other helpers in the latter year of diminishment. To satisfy the curiosity some no doubt are harboring, they are, in rough order of significance: direct sunlight, N-acetylcysteine, black cumin seed oil, niacin (which has the lovely effect of turning the skin bright red, and which is almost certainly what preserved my senses of taste and smell), Mg, melatonin (a potent anti-inflammatory), turmeric, raw honey, raw dairy, quercetin (with Cu/Zn), fulvic acid, ashwagandha, glycine, ginger root, zeolite, milk thistle, elderberry, and undoubtedly others that are not coming to mind at present (I am writing this at night, after all). Via this battery of helpers and other dietary considerations, I have only gotten sick twice in the past year. “But Paul, you’ve been sick much more than that!” I have been ill, yes, but not with foreign infections. I contracted some silly little respiratory thing in October for about a week, and I did again in December, for about three days. Everything else has been autoimmune or otherwise connected to The End. Some rather mock me for being sickly all the time these days. Fair enough: I am just a fool, and perhaps fools ought only to be laughed at. But via the above array, I very rarely was actually infected by anything (only twice in a year with significantly compromised immune function is not half bad). That my constitution is upended might be somehow inherently funny, but it doesn’t strike me as such.

Years ago, before every little flicker of sickness became comparable in social horror to the bubonic plague, I’d a practice of visiting sick families and friends. I rather fell into it. There would be plans for a dinner party, or a New Year’s party, or whatever else, and then the phone call would come:

“Oh, Paul, the kids had this awful flu thing, and they only just got better. We’re canceling. You can’t come or you’ll get sick!”

“Ah, interesting, but you’re not preoccupied with caring for them? They’re feeling a little better? Would you like to see me?”

“Well of course; we would love to have you but you might get sick and—”

“No, I don’t think I will get sick, and if I do, that will be fine too. See you soon!”

I got sick once, from doing this countless times; I had a bad cold for a couple days. Even into 2020, I persisted in this practice. Visiting people who had self-quarantined because of PCR test results or whatever other reasons—mere exposure to someone who had been exposed to someone who had, according to the grapevine, tested twice and gotten one positive and one negative, et al.; and in a way, it was even easier then:

“But Paul, you can’t come visit me! You might catch corona!”

“Ah, well, I doubt it, and it also doesn’t matter because it is more important that you not suffer alone.”

“But you can’t, you might miss work! Or you might spread it to someone!”

“Do remember that no one will bear to even see or host me; how could I give it to anyone? Who could I spread it to? And besides, I work remotely—who cares if I miss some work.”

“Paul, I can’t ask you to—”

“You’re not asking me, and neither am I asking you. I’ll bring materials and make us some cocktails.”

O yes, I lost a few friendships over such “antics” (as they were perceived to be). People talk, after all. Perhaps even then, I was presaging the fool into which The End would transmogrify me; but I was quite simply and simplemindedly attempting to, well, be Christian. I am nothing if not simpleminded to say this, of course, but if that word is Christ- + -ian, “like or of Christ,” and Christ spent His days milling about the leper colonies, I suppose the charge is that I dimly jumped to too logical a conclusion from the available possibilities.

But—I remember the eyes of those tired, lonely friends when I visited them. Theirs were not marred eyes of spent light. They—and not only their eyes, but their faces, their bodies—were aflame with Light.

And so, Light. It is time to recapitulate Part I | The End of the Beginning. The picture I chose therein was that of lights shining in the darkness. However, the head, or the theme, which I chose for Part I was death. But if to decapitate is to remove a head, what if to recapitulate is to appoint a new head, to crown a new theme? What if it is like unto a grafting, like being given a new family tree? And so let us baptize The End of the Beginning, grafting it into a new framework. In the closing section thereof, I highlighted the closing lines of its epigraph [emphasis mine]:

When the game stops it will be called on account of darkness. But it is a long day.

I then veered off into speaking about death, ends, means, etc. But I knew that we would come back to this place. What the lights incarnated unto my marred eyes was the Inexorable Fact that the game had not stopped—not yet. Yes, Thanatos was very much present, but the darkness was not. There was yet Light. The long day had not yet melted away into twilight. Even death could not stop the game—the Pageant, the Masque, the Liturgy of Life—which coruscates all about us, at all times, in all places. The glory of which ever shines upon us.

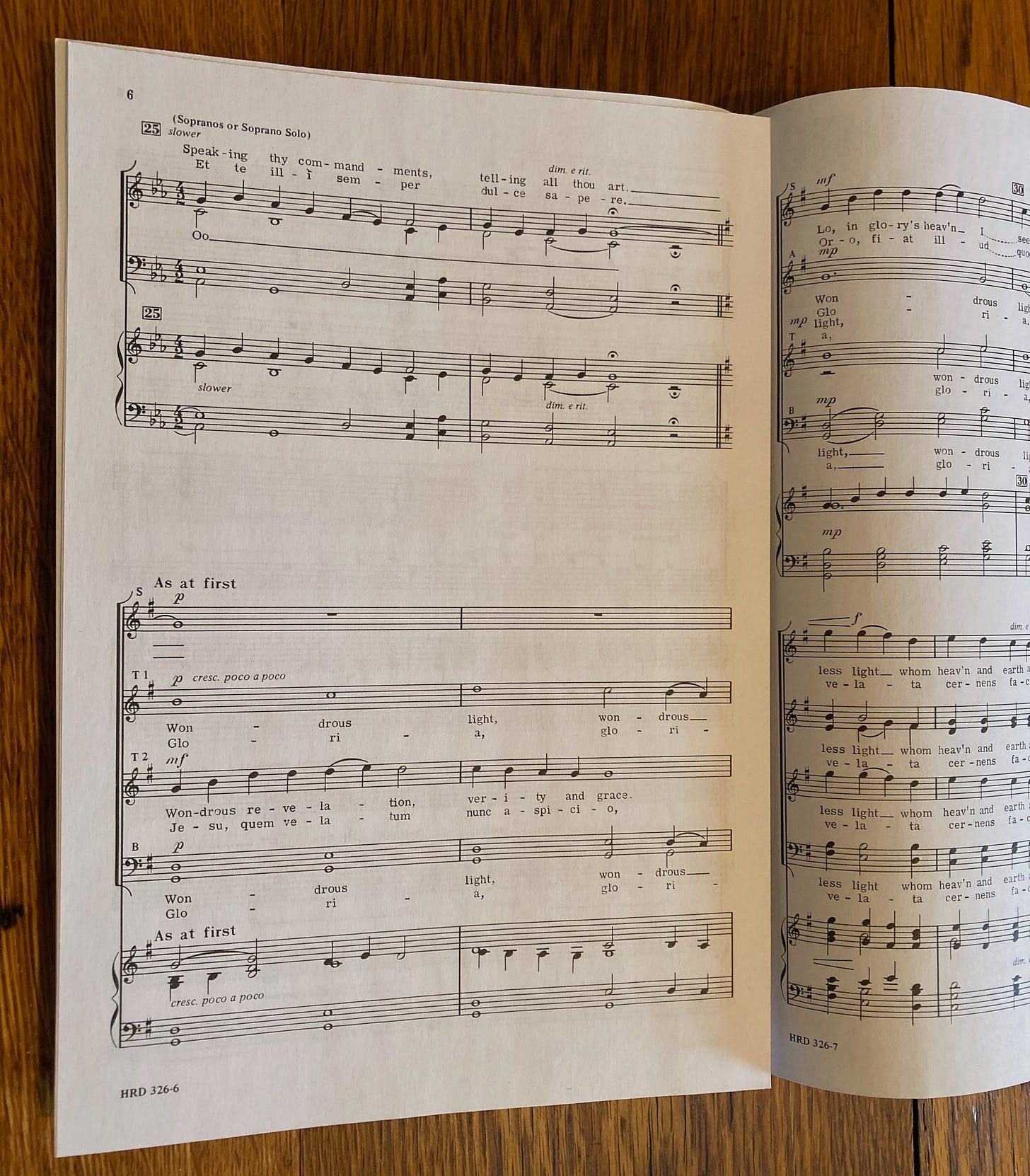

I have hitherto refrained from musical allusion in A Death Observed, but we are long past the death now [n.b. as in all my writings about music, my hope and assumption is that the reader listens thereto before continuing]. All Creation shimmers with song—as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be. And, plopped upon my bed though I was for those delirium-drenched days and nights of spiritual oblivion, this work often drifted through my head. And so did the memory of a ragtag group of us, many years ago, on a windswept winter day in Manhattan, singing this on a dirty street corner to pass the time. We fell apart a bit here and there, and especially at the climax, because there weren’t enough voices to cover the parts—but I am ahead of myself. In the second stanza, Aquinas writes (rather, the published translation renders): Taste and touch and vision, to discern thee fail; faith that comes by hearing, pierces through the veil.

Now, this line had a rather piquant glint in my dulled mind, because I rather dispassionately persisted in thinking to myself, “All fine and good, taste and touch and vision are all but gone from me now anyway—but hearing is gone most of all, so that veil is looking a tad impenetrable presently.” But while I knew the rest of the poem, I of course could not hear it—not really hear it, not Behold it, not Understand—not stand under—it. For I was deaf. But I would get out the score and look at it, reading it. Conjuring the sounds in my head as best I could. But it was not until I got it out today, weighing if I would include a photograph of it here, that I saw the words: As at first.

For this is the fulcrum of it all. In the previous verse, the English text has ended on a rather dry, creedal note, and the music is coming off of a dwindling series of ritardando, repetition, and fermata. But. But then, the sopranos do not cut off. Their final two words, thou art, pierce the gaping void between verses. And, even more gloriously, this piercing is not unprecedented; the tenors and basses attempted the very same, mere seconds prior, aided by the crown of the women’s unenunciated vowels. But that chord was askew; it was only an end—never a beginning. And so the choir tries again, this time built upon the men’s vowels, with the women now bearing witness. But here, here at the end, unlike the first attempt, the other parts die off. Their numbered beats flower, and then fade. And the sopranos, alone, calmly and quietly shine, adorning that brief fraction of Eternity—of uncountable Time composed of unaccounted beats—with the shimmering major third of E♭ major, our key hitherto. For thou art—I Am—likewise yet Shines in Infinite Perpetuity.

Then: As at first—is now, and ever shall be, world without end—the soprano G yet shining, and then, all about her, a G major chord explodes into existence, the tempo quickens, a rapid crescendo begins, and Time itself is collapsed inward by the music. While some of the tenors sing the poem: Wondrous revelation, verity and grace; other parts chant, Wondrous light, wondrous light. Then the sopranos seize the next line, Lo, in glory’s heaven I see thee face to face; and only they sing that melodic wonder, floating above the growing roaring chorus beneath them of quicker and quicker chants of Wondrous light, wondrous light, for there is no more Time, not anymore, for the clean and methodical passing of poetry between vocal parts as in the prior stanzas, for Time has come undone, and in the Splendor of Infinite Perpetuity, all is tumbling joy, and then—Light of endless light whom heaven and earth adore, begun before the basses even have time to finish their chant, but they do catch up in the end, and All is Light and Radiance.

As at first. The opening lines of the poem: Jesus I adore thee, Word of truth and grace; Who in glory shineth light upon our race. In my thoughtless delirium, I had latched upon the words, Taste and touch and vision…, and I had forgotten that which came before. I, drowning in The End of the Beginning, had misplaced both The Beginning of the Beginning—Jesus, Logos, Word of truth and grace—and The End of the End—Radiant Light Evermore, Lo in glory’s heaven I see thee face to face, Light of endless Light whom heaven and earth adore.

And yet, the lights. These little hanging strings of lights, quietly shimmering and dancing, utterly unconcerned with the world around them. They had not forgotten. They misplaced nothing. They pointed, quietly and faithfully, to the Light. Jesus I adore thee… who in glory shineth light upon our race… Light of endless light whom heaven and earth adore. Note too how the poem translates the first-person singular into all of Heaven and Earth.

I did not entirely miss the mark, though. Taste and touch and vision to discern thee fail; faith that comes by hearing pierces through the veil. Be so kind, please, as to remember what I wrote in Part II’s closing about the visitors’ words: but their spells’ veil had been rent asunder by His Word [“Not yet”] in a fashion not unlike a certain curtain of old. I then went on to indicate that that Word marked the first recapitulation of the misplaced Concept of Hope. Now let me show you the second.

Throughout the balance of The End, during all of Advent AD 2021 and beyond (and before), Penelope was crushed beneath postpartum depression. She was adrift in storms of insomnia, physical exhaustion, spiritual depletion, and—well, I needn’t define it. Unlike my exotic idiosyncrasies, hers was a more conventional plight. She and her family live a good distance from me, and we never saw each other during my time of crisis. However, the Authorship of God needn’t geographic proximity in order to speedily work. As I labored, in fits and bursts, towards healing, post-IVM, post-SARS2 infection; as I began to assess the damages, much less consider how to repair them—if repair were even possible—I came to know the unknown loss: I came to sense the spiritual hollowing which had transpired. The thought did not then occur to me that perhaps it was, in a small, quiet way, a hallowing, as well. As I began to realize how much had been lost—as the blissful unknowledge alchemically devolved, like gold to lead, into painful knowledge—I realized I did not know how to fix it. I did not know how to even begin. How does one begin to reconstruct humanity, to rekindle emotional and spiritual sensitivity? Surely yes, God transforms hearts of stone into hearts of flesh; but what if your heart appeared to disappear entirely, only to then reappear, but in a different shape than before? The one sensation of which I had both extant and intimate knowledge was suffering. I knew pain well by this time. And so, rather than divine how to begin to feel human again, I took another road. And, beholding Penelope from afar, seeing her testify to praying ceaselessly for my healing amidst sleepless nights of insomniac malaise, I pled to God the Father: take her cup and pass it unto me. I heard nothing—which is to say, I did not hear anything resembling, Not yet.

I shall not attempt to delineate the howling dark that followed. I’ve no desire to etch an image of that peculiarly feminine depression which was poured into my soul, that depression born out of the mixing of blood and water of mother and child, of root and seed, of labor and love. Women would tell me I did it no justice; men would tell me I am insane; and both, no doubt, already are in agreement on that latter point. And I still remember Penelope excitedly writing me one day, exclaiming that the night before, she had slept through the night, that all the clouds of hurt and noxious, inarticulate anxiety had melted away out of the blue. And I smiled a wan smile. The cup, though, did not find full satisfaction in me. It, after a time, returned to her, and lingered for no small number of days after. Like a game of ping-pong, she and I would pass the cup between us; for I did eventually let slip to her my prayer. And later, of course, she got around to reading the book from which I got the idea in the first place: Charles Williams’ splendorous Descent into Hell. Therein, Williams resurrects a doctrine of the early Church: that which he calls substituted love. He takes the, to my sensibilities, very plain and sensible approach, of interpreting St. Paul’s imperative that we bear one another’s burdens to mean just that: bearing them. Not just praying for people, or giving them a casserole dinner, or sending them a postcard with Thomas Kinkade’s effusive palette practically oozing off the card stock—no, bearing the burden, lifting it off of their arched and failing back, hoisting it upon ours, and literally bearing it. Now, I recognize that this is, to many, possibly an idea so absurd as to be beyond the pale. Luckily for you, I haven’t the least interest in attempting to prove anything to you. I am, herein, simply a storyteller: or, to be more precise, a witness. And witnesses, being already in possession of the Truth themselves, needn’t defend it; for the Truth, being a lion, is more than capable of defending itself (St. Augustine).

This infusion of another’s pain—and such illimitably foreign pain at that—poured fire down from Heaven upon the waterlogged wreckage of my soul, and the fire consumed all: the wreckage, the water, everything, and New Life, Vita Nova, blazed out in radiance, star after star precipitating from the sublimating waters, and the constellation they formed is called Love, for many waters cannot quench Love. And I remembered Kierkegaard’s assertion that the Christian must fully, wholly love the world and all that is therein; but that in order to love the world, the Christian must first entirely abdicate the world and all that is therein—to effect Infinite Resignation—for only thereby could the Father then return everything that had been lost, tenfold over. And I realized that the unknown loss had been, in a sense, the loss, or abdication, of everything; and I realized that the meteoric advent of fire in my heart was, in turn, the return of what had been swept away by the waters of anguish. O but how much more besides had been returned! A richness, a depth, a gravity, of empathy, of emotion, of knowledge, and, I dare hope and perchance to dream, wisdom. As in the epigraph from Middlemarch, I had fallen into that roar which lies on the other side of silence; but rather than die from hearing the roar, it was by dying that I was given the ears to hear that roar of coruscating, variegated Life.

However, some may find it untoward or uncomely that I, upon being delivered from the worst of The End, then immediately prayed to be deposited again into mire. Let us thus baptize Part II | Spent Light in Marred Eyes.

Throughout the period of, as I put it earlier, being dead, this modest, plain hymn rang out in the vacant halls of my mind. I had no emotional connection to it any longer, of course; I simply had the intellectual and sensory memories of having this memorized, of singing it in a quiet little small town’s choir. Memories of the soprano who would, at the close of the third verse, with the tenors’ glowing counterpoint dwindling away, turn her head to catch my eye, hers sparkling with warm delight. Fear not: I shall not launch into another idiosyncratic analysis of the music. Of all that I wish to comment on, I shall elect only two sections. First, the penultimate line of the hymn, So to my God I yield me; I highlight it here only to remark that it shall be addressed further on. Second, the opening of the third verse: What God ordains is always good: Though I the cup am drinking // Which savors now of bitterness, I take it without shrinking. Was it untoward and uncomely to seek out Penelope’s cup before my own was even empty? Perhaps that argument could be made, although the rebuttal could be made that mine shall never be empty until In Paradisum Deducunt Me Angeli. I do not care about arguments. The bitterness of the cup, not unlike the thorn of St. Paul, is but a sign of that grand Truth: My grace is sufficient for thee: for my strength is made perfect in weakness. Better to be a weakened instrument of God’s Peace than a strong and empty vessel. Better to love at great loss than to linger in perfect safety. Better to be a living sacrifice than an undying Narcissus. Better to drink the cup. Does not Christ offer Himself through a cup?

By my reckoning, there are at this point at least two fully-grown African elephants in the room, contentedly traipsing about, wondering when anyone will ask after them. Like Solomon, let us cut the metaphorical baby in half. I will comment in part on both elephants: one by explication, and one by implication. On September 27, AD 2022, ten months after The End, I wrote the following to some friends:

I started to go deaf again in the mangled ear. It happened so quickly. The pain is growing; some inflammation in the jaw, too, I think. The pressure compounding. Eye wants to shut. Please, if I may so trouble you, pray that the nightmare does not recapitulate. I am so weary.

You see, The End happened not once but twice. The second time, however, by means of either prayer or physiology or both—for the means were only vehicles of The Spirit anyway—The End was ended before it could begin. Encroaching, stalking death was dragged out of the shadows and put to death. The second time, The End lasted only a night. The second time also elucidated much of what the first time perhaps was.

I live in a house built as two apartments: a first floor, and a second floor. The forced air heating is all on one thermostat, all on the same shared ductwork. The air which is pushed into the second floor, where I live, is intermingled with air directly from the living spaces of the first floor. There are no air filters of any kind between the two floors: it is simply open ducting. And September 27 (AD 2022) was either the day after, or the very day, on which the heat in the house was turned on for the cold season.

Now, thus far, I have been careful to note that my symptom cluster was novel, exotic, unprecedented, etc. And that is, to the best of my knowledge, true; but note the grammar: it is true that the cluster was novel when I was, say, gobbling overdoses of painkillers. I have never said that the symptoms remained novel. Because they did not. By, oh, July, perhaps, AD 2022, there was a turning. And I began to find medical literature, clinical reporting, that matched subsets of the hell through which I had passed and, to an extent, continue to. Virtually all of the literature was published in other nations, such as Italy. There are two germane qualities of this literature, and only two, which I shall take time here to point out. One, the strangest of the symptoms (e.g. certain peculiarities of the tinnitus I have, and other disorders of the nervous system) were manifesting exclusively amongst those who had received immunization injections against SARS2; in those cases, painstaking statistical work had been done to show that WT SARS2 did not produce those symptoms. Only the injections did. Two, some of my more debilitating symptoms were appearing almost exclusively in autopsy reports. The patients, despite hospitalization and all of the interventions implied thereby, were all dead.

To those two qualities I have pointed out, I append two facts, neither of which is likely surprising: One, I am not dead. This, I trust, is not surprising. Two, I never received any SARS2 injection, much less even a single SARS2 test.

Contrary to popular belief, viruses are fragile things. People often conflate them with bacteria, because bacterial infection, viral infection, infection infection infection, it’s all basically the same, they make you sick, etc.; but this is not the case. Bacteria, especially bacteria such as Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax, are incredibly robust. Once they sporulate, they are capable of resisting radioactivity, much less wild temperature swings, the passage of thousands of years, isopropyl alcohol, etc. Many viruses, conversely, disintegrate in direct sunlight. Alcohol shatters their structure. They are fragile, for their design is not to linger in the environment, but rather to pass from host to host, expediently and efficiently. Sure, some can linger on some surfaces for some number of days, but compare “a few days” with B. anthracis’ “hundreds of thousands of days.”

Let us return to my ductwork commentary from before. Thought experiment: let us pretend that WT SARS2 were somehow capable of incurring a symptom cluster on me which medical literature has flatly proclaimed can only arise from the SARS2 shots alone. Then, let us imagine that on September 27 (AD 2022), when my world began to violently contract into nothingness yet again, it was because the reactivation of the furnace had expelled lingering WT SARS2 from the ductwork, allowing it to penetrate my sinuses and Eustachian tubes and, well, play it again, Sam. Fun thought experiment, but SARS2 is far too fragile a virus to persist for over a hundred days in the ductwork. Contention: “maybe your neighbors coincidentally had SARS2 in late September, Paul, and when they turned the heat on, … etc.?” Fun contention, but I was around them several times during this period, and they were perfectly healthy.

Second thought experiment: let us do the first experiment again, but this time substituting November 20, AD 2021 for the date. Well, my neighbors were not sick with SARS2 then, either. And while this second thought experiment does not necessitate WT SARS2 particles to persist through ten dozen days of environmental exposure in ductwork, it still does not resolve how said particles could have conferred symptom clusters which WT SARS2 cannot confer. Besides, the first time The End happened, my neighbors were gone. Or rather, to be quite specific: they had left that very first day, on November 21. They had left to go visit extended family whom they had not seen for quite some time (due to SARS2 concerns) and generally trundle about for Thanksgiving etc. All well and good. If I am not mistaken, it was the practice of many, many Americans in the fall of AD 2021 to get the SARS2 shots out of either concern for their elderly relatives (or themselves) or due to direct mandates from employers. It is not beyond the pale, then, to imagine that just before departing, my neighbors had partaken of that therapeutic route. After all, at least one of them works for an organization which, if I am not mistaken, had an employee mandate for the shots at that time anyway.

How, the reader asks, does any of this change the outcome of the thought experiments? How could material from the injection make its way into the ductwork, up a story, and into Paul’s home? Well, it’s been tidily established that those who have gotten the injection can “shed,” or slough off, the SARS2 spike proteins which the mRNA shots direct one’s cells to manufacture, well, billions of; and if such shedding were to occur via the medium of exhaled aerosols, the spike proteins would be as conducive to airborne transmission as any other common virus. To those who would dispute shedding, I would quietly reply that for many, many months after The End, any extended (20+ minutes) proximity to people who were actively getting the shots or boosters would dramatically enlarge the tinnitus and dull ache of my ear and head, often inducing enough stress on the nervous system that severe nausea would follow. I went home from dozens of church services profoundly sick, and it was easy enough to test if it were arising from proximity to specific people, and it sadly was. Another contention: “but Paul, even supposing you breathed in a bunch of highly refined, highly concentrated SARS2 spike proteins, how could that cause what happened to you?” I will answer this with a series of wandering remarks, but in short, I believe that what happened to me is nigh unto indescribably improbable (but clearly not impossible). The spike protein is responsible for the vast bulk of SARS2’s pathogenicity. It elicits hyper-inflammatory reactions which cause cell death (via mitochondrial damage et al.) and organ failure; it tends to accumulate in the heart, liver, and kidneys, and it can bypass the blood-brain barrier; and—most importantly for our thought experiment purposes here—IVM has been shown to severely attenuate the pathogenicity of the spike protein. Remember, if you might be so kind, just what it was that put an alacritous end to my tailspin towards oblivion.

If it is not already clear, the elephant in the room of which I am currently speaking might be titled, “But Paul, how did this happen to you—what even happened?” It is logically absurd, if not outright obscurantist, to not hold that the SARS2 spike protein is the root, the radix, of The End. And the simple, indisputable fact is that there are only two sources for the spike protein: WT SARS2 and the mRNA injections. Both serve to hijack the intracellular machinery of one’s body and redirect cells into the manufacture of spike proteins. Both have well-established symptom clusters and side effect profiles, respectively. And given the highly inconvenient fact that I have had, in discrete episodes, the symptoms of each, and yet demonstrably ought only to have had the symptoms of one, hypothesizing necessarily follows. If you find my hypothesizing offensive, after having read everything until now—counting, evidently, The End to have been a trifling thing—then I invite you to divine a means of going through what I went through and perhaps thereby realize how (dis)content you are to settle for the nonsensical, obsequious haruspicy which passes for so much “medical diagnosis” nowadays. Let he who has drunk of this cup cast the first stone.

And I will go one step further, having nothing to lose—having a soul bathed in the fires of living sacrifice, a mind shattered upon the anvil of ego death, and a body branded by searing bands of death—I do not necessarily believe that it is shed spike proteins which I breathed in, which passed through my nose, which wildly, wildly improbably evaded every element of the innate immune system, which melted into capillary beds in my sinuses, which set off mast cells, which triggered an explosion of autoimmune meltdown for months. No, I do not necessarily believe that spike proteins could do all of that—not for as many days as The End was. And I am not so sure that the spike protein could persist in the ductwork for that long, either. But what if there were an engineered substance, a molecular vehicle for a means to produce many, many spike proteins? What if such a vehicle had been designed to be shelf-stable, to be robust, to resist molecular breakdown? Could it persist in ductwork for months? Maybe. Who knows? I doubt anyone does. Ignorance is pleasanter than perjury.

The contents of the SARS2 injection have, in anecdotal cases (but do remember that all of “science” is nothing more than the collation and publication of anecdotes), been shown to be transmittable. I have focused on my house’s ductwork because it is a ready, small-scale example; but please do not presume that I lack the imaginative power to enumerate dozens of other putative vectors for my having been, shall we say, poisoned. The trouble with being too descriptive, of course, is that necessarily, specific people may begin to feel responsible.

Of course, all of this is mere hypothesizing. It is simply my lining up enormous ranges of disparate facts and chronologies and logistical constraints, finding the most logical explanation to simultaneously satisfy as many of those constraints as possible, and then seeking—desperately seeking—to be proven wrong. And thus far, every new piece of literature which I come across only bolsters my reasoning, polymorphic though it be. In early December AD 2022, when one of my eyes spontaneously began to bleed, and continued to bleed for about a week despite no signs of infection or injury, is it a coincidence that it was my right eye? A couple days into the bleeding, while looking up something utterly unrelated, I stumbled upon a preprint study whose title went something like this: “Retinal Hemorrhage following SARS-nCov-2 Vaccination.” I laughed and laughed, and continued tending to my eye as I had been, and it healed a few days later. The blind squirrel may occasionally find a nut, but what about the blind squirrel who can’t stop having them fall on his head? About ten months ago, while glancing at the august Star Tribune for news of Minneapolis’ reconstruction efforts following the destruction wrought in 2020’s violence, I instead stumbled upon an interview with a Mayo Clinic Senior Administrator of Vaccine Such-and-Such, and he was candidly describing the causative relationship between his receipt of multiple SARS2 shots and his crippling tinnitus. He, the consummate materialist, concluded by assuring the public that the shot was inarguably safe, effective, etc.; and yet he also said in so many words that the tinnitus was worth it, and he seemingly embraced the tinnitus as ineluctable and terminal. I am unsure that I know just what he meant by that antecedent-less little pronoun, “it.” I am unsure that he knows, either. But I resolved to not take his road of resignation. To accept, to acquiesce, to some obtuse sentencing of sensory wreckage? No. Man was made for more than this. I continued as I had been. After all, about two months prior, I had found a disturbing case in the UK: a patient had suffered all but one or two of my symptoms of The End, and he had a couple others besides. Despite over a hundred doctor’s appointments and hospitalizations, and a dozen or so surgeries and procedures, over the course of about a year, his condition was only worsening. I wonder whether he is still alive. He and I chose very different paths, after all. And I continued, as I had been doing for many months already, my meandering, straggling quest towards the restoration of my body. For with my eyes shall I see God.

But this is all more than enough science for me. After all, ostensibly that is what science is: hypothesizing. And I tire of it. At the end of the day, long day though it be (according to Robert Penn Warren), the source of my diminishment does not much matter to me. I am content to call it the plague of SARS2, whatever derivation or form thereof it took. To any who may simmer with belligerence, excited to contest any I have written, I only mildly remark that I have not nearly rendered my full evidence and reasoning for musing as I do. Do not suppose that I have exhausted my microbiological knowledge in a handful of sideshow paragraphs of a kaleidoscopic spiritual biography. Some have asked me what I think happened to me because they wish to take measures to protect themselves or their children from my fate. That is the only reason I write any of it. To honor the love of those who seek after Life and hope to have it Abundantly.

The third baptism. But I have come that they may have Life and have it Abundantly. The Greeks had their εὐδαιμονία; the Romans, stoicism; the Christians, Abundant Life. So often, however, I have suspected that we know not that for which we ask. What is it to have Life Abundantly? Elsewhere, we are told that those who lose their lives will gain them; cf. Sophocles’ comment (in the epigraph) regarding death being a “rich reward.” For the Christian, is not death a rich reward, on account of death being merely The End of the Beginning? But: who among us asks to die? The final musical baptism of this Observed Death is unlike the others. It is florid, it is pastel, it is romantic, it is impassioned, it is wild. It is the only I’ve not sung, much less memorized. And it is the only which I shall subject to a little deconstructionism (with apologies in advance to the school of New Criticism).

The tone, the timbre, the aural, sonic quality of this work, rings out in perfect unison with that of my diminished frame. The sensation of my mundane existence, my day to day life, is that of a candle washed out—occluded—by the noonday sun, of a snowflake devoured by the crashing breakers which confer the salt necessary for one to become the salt of the Earth. On many days—not most, but many days—to even breathe is pained, with either my nasal airways inflamed or my lungs aching from lingering ghosts of autoimmunity. This is, I suppose, one reason I adore choral music so much. If to even breathe is to be condemned with pain, mayn’t at least beauty arise from the ache? If hearing is condemned to be forever plagued by ringing, why not sing, covering over the gaping void of abyssal tintinnabulation with shimmering beauty?

It is my impression that many Christians seek after the subject of this poem: to be lost in love with God, to be lost in the love of God [to be briefly deconstructionist, let us make the poem about the Christian God]. And I do not in the least condemn them for seeking it. Drowning, however is not an easy thing: O plunge me deep in love. Because then the poet goes on: put out my senses, leave me deaf and leave me blind. And I am unashamed to admit, for I’ve precious little pride left in these days of ego death, that I never asked to be swept by the tempest of [His] Love. I certainly never cried out, put out my senses. And yet that is what the Author deemed vital for His Grand Pageant, His Great Comedy: my diminishment, even unto being a fool.

And such is my lot, and I cannot forget that we are to be fools for Christ, and my faintly flickering knowledge of the Major Arcana, of the Greater Trumps, reminds me that the Fool is ranked, if at all, as 0. And thus the span is numbered, from 0 to 21, from the Fool all the way to The World. And we are to love the world, and perhaps that can only best be done by diminishment, by becoming but a taper in the rushing wind. By becoming the Fool.

But unlike the poem, I will go further. The choir drifts off in quiet abdication at the end: but not lost in you. But I have already abdicated all. I have abdicated and watched it returned. I have the boldness to say, but now lost in you. And not, as the poem’s title mourns: I Am Not Yours, but rather, I am now Yours. For a single consonant can make all the difference in the world.

When I began formulating this work in my head, many months ago, I had settled from the very beginning on this title: I am now Yours. Of course, that was before I elected the tripartite structure. And over the course of dozens of insomniac nights, I lay awake and chiseled away at the heap of marble wreckage which had been strewn about my heart and mind by the floodwaters of encroaching death. I picked and prodded at thoughts, moving them here or there, staring up at the ceiling, or staring off to the side, where the visitors once lurked; and all the while, I could only hope that that which waited, trapped within the marble, might be a Good and Beautiful Thing. For what else ought we to make than that? And it was over a year ago that a friend offhandedly remarked, “Paul, you should write down what happened to you when you were sick.” He was under the impression that I had recovered, that I was better. And I may never be again—not really. Only One knows. But to press the issue would be to interrogate the Architect, and I’ve no interest in that endeavor. I simply tend to the temple which I have been given, seeking its welfare as best I know. As that temple, my body, falters and often fails, and the blood and the water of mortality can so tempestuously assert themselves, I am, in my most blessèd moments, merely serene. When one once believed that hearing, his most precious sense, was inexorably, inalterably lost, and then hearing (in part) et al. returns, one becomes much more content, or satisfied, in the face of buffeting trauma. Satisfied. From “satisfaction,” from Latin; the whole splendid etymology, I’ll not bore you with: “having been made enough.” I am satisfied.

A friend remarked to me recently: “I just got over being sick for a few days, and being so tired and worn out from that—it made me think of you, and how—what—you’ve, what it’s been like—” And it is true. I am so weary. I am so tired. It has been over a year of waking unrested, of sleeping restlessly, of smeared thoughts, dashed hopes, and dwindling resources. Of so much pain. Of profound depletion. But it has been a year of miracles, of helping to heal others, of seeing life spring into the marred eyes of the hopeless, of beauteous, beauteous fighting: simply by virtue of not giving up. In The Fall, Camus makes mention of how life can become such a violent, twisted, difficult thing that to continue for even five more minutes is a superhuman act. And Camus, as in many other cases, is not wrong here. Is the poet wrong? He writes,

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

In matters of Earthly import, mundane business, vulgar affairs, I consider Tennyson far from incorrect. But in matters of Divine import? In the matter of A Death Observed? No, dear Alfred; I am sorry, but you are so very wrong. To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield? What an impossibility. No man has sufficient strength. No man could endure. Soon enough, and sooner than any would wish to admit, to continue would be Camus’ superhuman act.

But what if I were wrong? What if the poet were right—accidentally right, yes, but right nonetheless?

For there is one Man with sufficient strength. One Man capable of enduring.

And so I shall strive, and I shall seek, and I shall find. But to not yield is an impossibility.

So to my God I yield me.

Twice the matter has been raised, and twice I have brushed it aside. Yet, just once more, let us entertain: what is the Architect building amidst the wreckage of The End? I could not presume, but perhaps another, braver, holier soul may. Perhaps one from that Great Cloud which ’round us alway sings, if we but had the ears to hear. Perhaps it is folded into the euphonies of that roar of which George Eliot so delicately wrote. And perhaps I do dare presume, Fool that I am. But; do you remember the Greatest of the Greater Trumps? Behold it here: behold The World, behold The End of The World. Here is the end of death. Here death ends.

Then Sin combined with Death in a firm band

To raze the building to the very floor:

Which they effected, none could them withstand.

But Love and Grace took Glory by the hand,

And built a braver Palace than before.

- George Herbert, “The World” (AD 1633)