Blade Running, VHS tapes, and the meaning of life

Retiring some fetid misconceptions about teleology.

It’s been a while. As ever, remember that I bury the lede. The props need to be set in place before the play may begin. My writing is not for the academicians who crave a clear opening thesis statement.

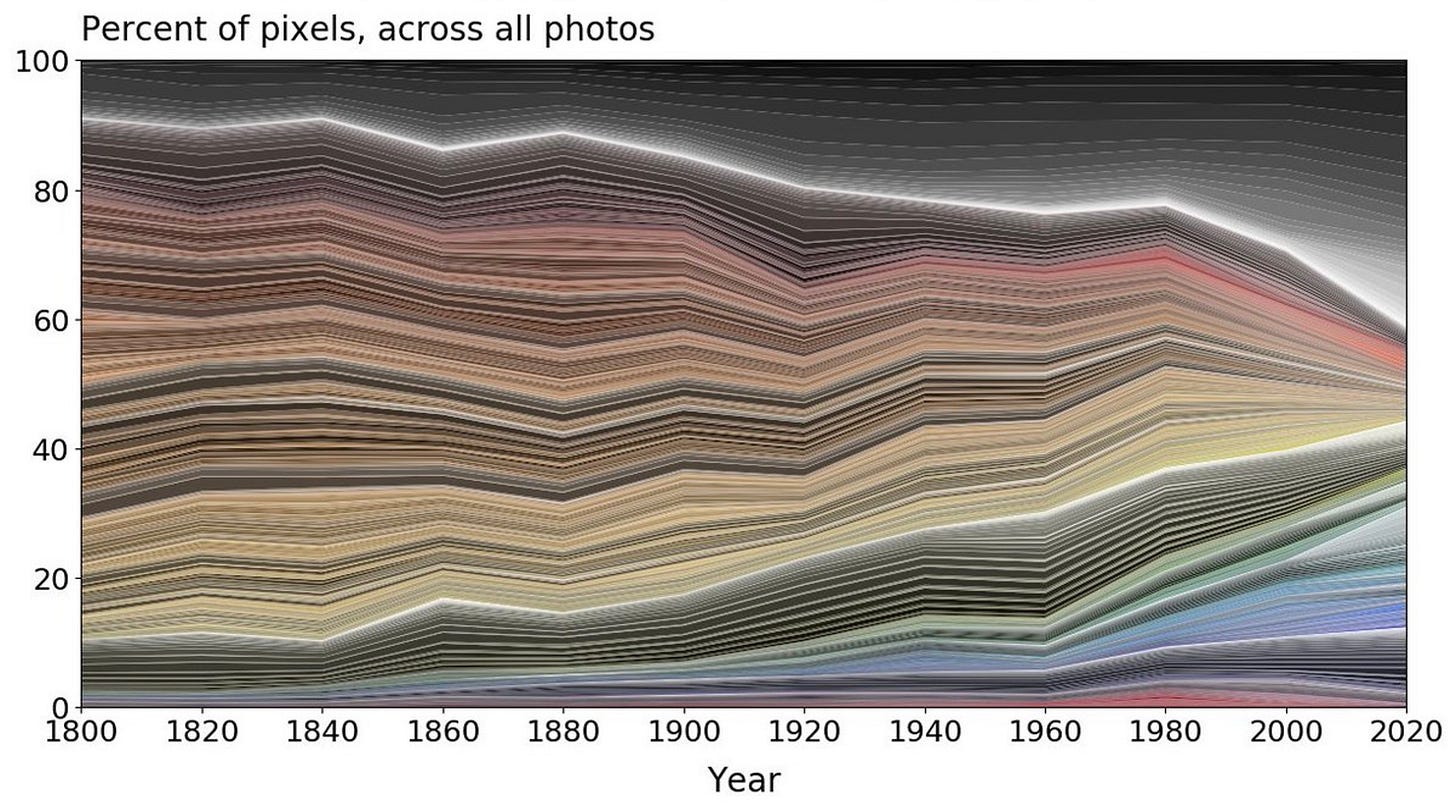

Once upon a time, there were these colorful, brightly lit stores scattered all about the United States. They were adorned with movie posters, their end caps bursting with B-movie shlock and various candies, and gumball machines flanked their sliding-door portals. It’s been so long that I don’t remember the exact price to rent a VHS tape from Blockbuster, but I remember enough to know that the price was much less than that of a modern digital rental from the server farms of Amazon and the like. This was back when the world still had a great deal more color than today; this was long before September 11, AD 2001, longer still before the Great Recession, longer all the more before AD 2020 and The End of, in many senses, [Western] civilization. Notice in the below how the solar colors—colors of life, the reds, yellows, oranges—are compressed by the squeezing grasp of cold blues, piercing whites, and howling blacks. Our world is becoming, quite literally, desaturated.

Recently with friends, I watched both Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049, both via 4K BluRays. The medium is not unimportant. For me, films remain physical artifacts, not fleeting digital ephemera of streaming services, just as the internet remains in my mind a physical construct: a physically linked network of computers whose nerves are copper wires, and whose skeleton, DNS servers, switches, routers, etc. Many of the younger generations today treat the internet as a fourth dimension—as a permanent, wireless, ethereal [cf. “ethernet”] layer which sits atop and amidst the physical dimension. To me, the internet is something which comes out of a wire, just as a film is something watched from a VHS tape or DVD. It is physical.

When you would rent a VHS tape from Blockbuster (or any other rental joint), there was always the thrill of gambling. You would pry open the little rectangular plastic case, and there was the VHS cassette, and you would see where the tape was. Was it all on the left or right spool, or somewhere in between? Like the shopping cart problem of today, there was once the VHS tape problem: when you’re done watching the movie, did you rewind the movie before returning it?

VHS tapes are gloriously analog: when you rewind (REW) or fast-forward (FF), the spools simply spin faster, causing the magnetic tape to be pulled across the VCR’s video heads at a quicker rate, causing the images to fly by faster and faster. When you REW or FF a DVD, the images will jump, not accelerate smoothly; this is because being digital, the data cannot be perfectly smoothly translated into motion. It is not physically tangible like a magnetic tape stretched taut across spools; rather, the data is being plucked up by the DVD player’s laser physically jumping between discrete storage sectors on an optical disk. This is the same reason why any attempt to recreate the iconic record-scratch effect out of CD playback results not in stylistic novelty but a destroyed CD. We shall return to VHS tapes; first, variable adventures in cyberpunk AD 2019 and 2049 are requisite. I shall avoid spoilers as best I can; I recommend both films, but for those who care, I do note that both contain unflinching violence and, shall we say, the unrobed human form. (But are the forms human if the figures are not? A question for the philosophers.)

Both Blade Runner films linger, seriously and nigh unto painfully, on the subject of memory. So much of our inner [and exteriorly realized] lives rely upon the gravity of memories. Our actions orbit our hearts, and our hearts are held together by this gravity. How we treat people is moderated and mediated by—occurring via the medium of—memory. How a person has treated us in the past informs, affects, and effects our treatment of him in turn. In their own ways, each film asks and investigates the question: what if memories were manufactured? What if your own past were synthetic, a product of artifice, of technique? What if a memory were true—it were truly someone’s—but it were not your own? What if your heart were built out of fractions—one might say, built out of the fractionated bits of others’ hearts? What, then, are you?—and more radically, who, then, are you?

We men and women have a terrible tendency to look for REW and FF buttons in our lives. We often seek to REW to brighter days, to the more vivid colors of the less desaturated past. We seek consolation from the precarious present tense in the apparent solidity and tidiness of the past tense. So often, the past appears as a house built upon rock; the present, a house upon sand; and the future, a castle in the clouds. Feeling unmoored and buffeted by the dangers and unknown unknowns of life, we REW now and again to the past. “How has this person treated me in the past?—ah, yes, we met at that, right, that thing years ago—hmm, he insulted me, right—yes, that’s it, I don’t really like this person.” But we have to remember that we dislike a person, just as we remember that we like a person. We must remember to remember our own selves, just as we so often thoughtlessly define our selves by other selves.

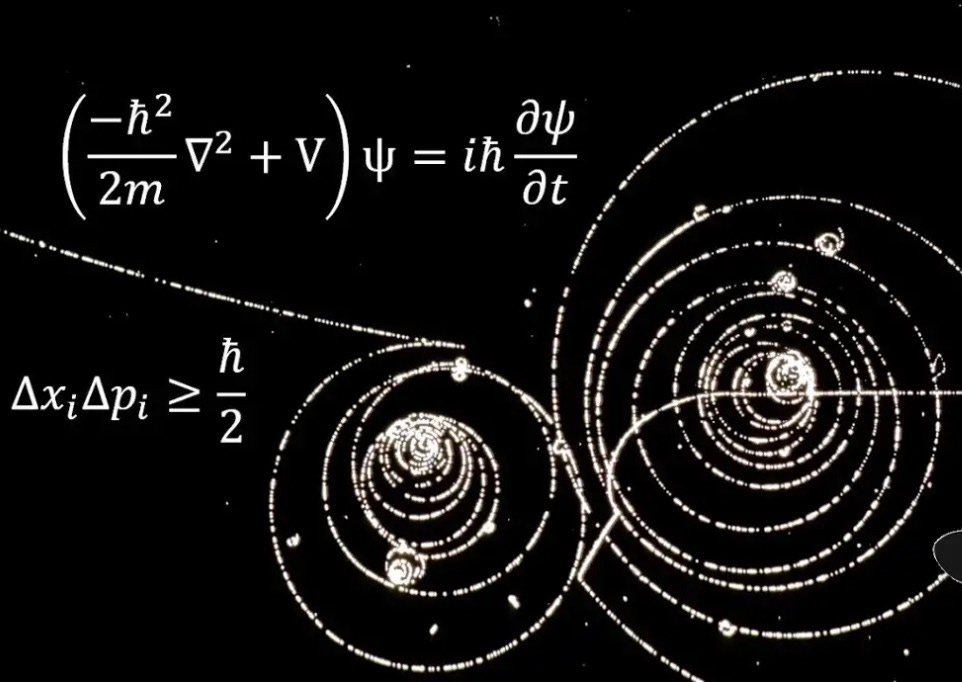

I dare suggest that perhaps we needn’t memory to be ourselves. We are, each of us, a self, and that self exists across time irrespective of memory. (Another filmmaker, Christopher Nolan, elsewhere argues that Love exists across time, but that is for another time, as is raising the question: might a self be counted a nucleus, or locus, of Love?) We needn’t film in order to raise this question, either. There are cases, for instance, of organ donation, in which an organ recipient gains memories from the organ donor: fears, nightmares, joys, etc. (It goes without saying that such phenomena ought raise into question the nature of organ transplantation.) There is also an argument to be made that some techniques of contemporary psychotherapy may cause a patient to auto-implant and internalize memories of childhood traumas which never even happened; but, of course, following such implantation and internalization, the memories become real, and the person lives as though such traumas did happen, when they in fact did not. Should a person experience such alteration of the past, what is altered is his self; he was a self before possessing such memories, and he becomes an altered self afterwards: but he possessed, and was, a self all along. He could, alternatively, have not undergone such alteration, and the self would have persisted. For a self exists purely in the present tense, for only the present tense touches—is tangent to—Eternity. The past is, of course, not real; and neither is the future. For how can you reach out and touch either a memory or a hope? Our world, despite our variably foolish wishes, is firmly incarnated; and flesh is a present, albeit fleeting, thing. Reality—realness—is a quality describing an instantaneous moment in time. We may touch a knotted log, lying molded and hollow in a forest, and say, “Ah, I know that this was once but part of a mighty tree”—but do we know that? The same sense-information which causes you to think you know that, cannot, in any fashion, prove that what you “know” is true. Someone could have placed that log there yesterday. God could have created it five minutes before you walked into the forest. My argument is not for nihilism, solipsism, or any such nonsense—in fact, it is the clear and bellicose opposite!—but for simple, candid consistency. You do not know the past. You may guess at it very reliably and surely, but it is not Real. You may not reach out and touch the log in its prime, and in simultaneity see what became of the log. You see the log as it is now; its past is murky. Its past was not given for you to see. Call it an existential Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.

You cannot rewind the tape of Reality. You were given such a time as this, and this is a moniker for a discrete, particular point in time and space. You were given for the present tense, and it, you. What if you forgot whether you disliked a person? What if every time you met him, he were new to you? I am partial to this line of thinking because, of course, it happened to me (as described elsewhere); I misplaced my self, my memories; or, more accurately, both it and they were taken from me. And I realized that I did not remember what I “thought of” people, because I had lost the memories. All I had to go on was the present tense. I could only know them by their fruits. But is that not what we are called to do?

Besides the temptation to REW, there is another, and I posit much more deleterious, temptation: to fast-forward. You likely know this phenomenon well, even if not by that word. You have just turned thirteen. You wish to be driving, to be in high school / secondary school. You crave independence. “I just want the next few years to fly by—O, then, I’ll have arrived! Then I can really get started with my life.” You wish to FF. Or you reach that milestone of youth, and then you look ahead to college, or to working: “Ah, if only I were a few years older, and then!—then things would really be exciting. Life will be full.” You wish to FF. How many years are lived in the desire of putting them, those very same years, away? How much boredom, that terrifying horror, is birthed of a desire for some vaguely defined future moment? Thoreau remarks, “As if we could kill time without injuring eternity” (Walden); and as our only interface with Eternity is its tangent, the present tense, how right he was! To falsely claim ownership of a thing is to abuse it, to injure it; and the future tense was not given for us to possess. We gleefully look upon the future through a murky, shattered kaleidoscope which we cavalierly call a telescope. We flail about, calling it prudence, or responsibility; we delicately feed and water our “5-year plans.” How easily we rehearse, “First, this will happen, and I’ll react this way, which will set me up for that, and after a couple years, I’ll be able to pivot to this, and—”

But none of it is Real. Go on: reach out and shake the hand of your new boss at the job you’ll get three years from now after you perform two diagonal promotions via jumping between firms. Shake his hand! Look upon his eyes, tell me their color; tell me the shade of his skin, describe how light glitters upon his hair!—you cannot, you cannot, you cannot!—because he is not real, because the job is not real, because none of it is real. You have discarded the precious gem of the present tense to grasp after the sands of the future, mistaking them for priceless glass. But lightning does not strike anywhere but the present, and there is not yet any glass: you’ve nothing in your hands but sand, untransmuted and common. And so it slips away through your fingers. And you grasp harder and harder, your nails digging blood from your palms, and still it falls down, dust returning to dust, streaked with the crimson wreckage of killed time. And you never see the glass menagerie all about you, the props awaiting the play, and the play is you.

Your life is not a VHS tape. Neither is your life even a DVD like those I watched of the Blade Runners. It cannot be spooled back and forth, jumping scene from scene, avoiding the murder and horror to see “the good parts,” the talk of glittering C-beams, the talk of whose the best memories were—no. Your life must be lived squarely in the present tense, one novel moment followed by another unknowable moment followed by an unimaginable moment. Behind you, in your wake, is a littering of glittering memories: some good, some not. Some true, some not. For even the healthiest and most well-intentioned among us fall prey to formation of counterfeit memories. Our minds, cramped and straining against the forceps of Time, make up what makes sense about the past. But what makes sense? Who decides what sense even is? We do. Each self does. And we’re often right, for our minds are sharp. But, to use the alliteration of the Latin: saepe non est semper.

Often is not Always.

We are not always right. Our minds are not always sharp. In the kitchen, it is the dull blade that finds your skin.

There is a sect, a branch of thought, rampant in both contemporary Christianity and scientistic materialism. You may find it everywhere from megachurches to Leonard Nimoy’s script in Star Trek. I count it heresy and folly, alternatively. It is that your life is not about you. To the materialist—much less his midwit cousin, the effective altruist—your life is about maximizing the good of “human” lives (either yours or the maximal number of others’ human lives). What is good? Who knows. They don’t. What is human? They don’t know that either. But this yeasty idea is baked into the cake of that drunken shibboleth: for the greater good. As Spock dispassionately recites, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” The historically unmoored Christians, meanwhile, might put it as: “Your life isn’t about you, because the Bible says you are dead; you need to love your neighbors and love the world and love God and lose yourself in such loves.”

With as much respect as I may muster, I disagree. And not only that, I decline. I decline to live in such a thin puddle of a world. The world, if it were a metaphorical body of water, is a glorious, tempestuous ocean—not a mud-laced pothole of two inches’ depth. Your life is entirely, singularly, about you. What’s more, it all may be folded, like origami, into something yet grander: it is about your relations with and towards the Divine. For to be in Christ is to be in His Bride; and does a Bride best love her Groom by loving everything else too?—being concerned with everything else too?—no. She gives all of herself singularly unto Him. Then the space and capability to love other objects bursts forth, as a flower unfurls her beauty before the rising sun. But the flower has to have first accepted an obligation unto the sun in the sky and the carbon dioxide in the air.

I hesitate to say “the point” of Blade Runner 2049 is such-and-such, so I shall resort to: an animating [soul-giving] conceit in Blade Runner 2049 is this: your life may be entirely about you, but you—you yourself, your self—may be about someone else entirely. You must live by your lights, treading through each moment and scene of every act of the play which is your life: you must lay aside any imagined remote controls with their manifold buttons, resign the falsified twin potentiality of REW and FF. You must face every moment as though it were all that is Real—for that is precisely the case—and, in short, you, you plural, all of you, must, truly, carpete diem—seize the day—but you must remember Whose the day is. It was lent to you, but in the end, at the end, you must return it.

Your life is not a VHS tape. There is no rewind nor fast-forward. You known’t the length, its span in years or decades; what you have been given to know is the length of a second, and that thirty-six hundred of them fill an hour, and that twenty-four of those mark the revolution of the Sun from East to East. Those we call Saints are those whose Faith affords them the power to measure and step athwart that infinite span from East to East: those whose actions transcend the material boundaries of incarnation. They are those who work miracles: for miracles, being Love, pierce the tapestry of time and place. But let us ignore the categorical and close with the specific.

In our retellings of the story, Joseph, owner of that coat of many colors, is the protagonist of his story. This seems intuitive, after all: of course the story of Joseph is about Joseph. His brothers, aflame with the death and decay of resentment, sell him to be trafficked far away, he ends up in Egypt, a bureaucrat’s lusty wife goes shopping, he gets jailed (but not executed, as the law commanded!—the bureaucrat was no dummy) for attempted canoodling, he interprets dreams, he is exposed as a hyper-competent type of e.g. Merlin, and as wizards are, he is elevated to the king’s side; but then what happens? Well, famine, as wasn’t uncommon; and his brothers show up, there’s some intrigue, a teary reunion, everyone lives happily ever after, the Israelites end up in Egypt, that doesn’t work out well in the long-term, etc., and that’s the story. Joseph is the protagonist of his story.

Sure. He is the protagonist of his story, and his story is, mechanically, about him, insofar as it does revolve around him. Picture it this way: a wheel revolves around an axle, but does anyone ever claim that an axle is the point of a car? Isn’t the point of a car, at worst, the car, and at best, whom it carries? And so we return to Joseph. His story is about him, sure; but he is not about himself. He, his wisdom, his cleverness; his being plucked out of the well and shuffled off to Egypt; he, the protagonist, was as a wheel on a car. In the wheel’s reference frame, the axle and wheel are all. And Joseph lived by his lights, and he performed admirably.

But Joseph isn’t about Joseph. Is Joseph about Benjamin? Joseph is about saving Benjamin from famine and death, because Benjamin was the other favored son of Jacob, and—

No. Joseph, the entire wheeling, multivariate cathedral of complexities in Joseph’s life, the coincidences and betrayals and twists and turns of fate and Providence: all of it was to manufacture the props and blocking of a single scene. It was to provide Judah, his brother, the opportunity to prefigure Christ. It was to allow a man to take the guilt of another, his brother Benjamin, upon himself, willfully and freely and—literally—unjustly. And, doubly, it was for Joseph’s grain-stockpiling public works project to feed the kingly line of David bread centuries before David would lay hand upon the showbread.

In the absence of Joseph’s Egyptian sinecure, Jacob and his seed—the promised seed—starve to death. There is no Judah. No David. No Jesus Christ. No crushing of the serpent’s head. All of history hinged on Joseph. But that was, of course, all in the future tense for Joseph. He knew it not. All he knew was that famine was coming. All he knew was that he was to forgive his brothers. All he knew was his own self, and God. All else flowed therefrom. To have fast-forwarded through the suffering of his life would have been to cauterize the line of the God-man. To have ruminated in rewinds of his happier days of many-colored coats and a delighted father would have passed by his glittering, appointed drama of feeding that same father life-saving bread.

Christ was bruised and broken into bread, just as He was trampled into wine. To save the life of Judah, Christ’s forebear?—Joseph too was bruised and broken into bread.

Ours may often be lots of great suffering. The suffering is variable, and the lots are not evenly distributed. Some draw lots with evidently little suffering; others, with little evident suffering, and so on. The lots fall as they may. Our role is not to question the Allotter. Our role is to play the role written for us, upon our hearts, before Time was birthed from the splitting of the sky between Day and Night. The meaning of life is to give the question of its meaning away. Refer it to the selfsame Author of every question and every answer. The script is in your hands. We were never expected to manage memorizing so many lines, so many stage directions: and so we were given the script. You may find it everywhere, for it is written upon all of Reality. Reality itself is written in the script: all is Möbius. Life imitates Art; and Art, Life.

What the Art is which your Life imitates, and vice versa, you may never know. Some are given the eyes to see; some not. But rest assured that your life is the wheel which delightedly orbits you, your self; and though you mayn’t know the greater narrative beats to which your life plays vehicle, there is something borne up above you, sheltered from the bumpy road by your bruises and agonies, that is being preserved and kept alive and aflame. It may be as simple as your own eternal Soul—which is no trifle indeed! Or it may be something altogether much more unimaginably greater—in which case you would be right to expect bandits on the road.

Fear them not. Martyrdom, white or red, may be appointed for you: shirk it not. But remember that to choose martyrdom is to negate it. Your role is not to choose, but to roll ever onwards, running that good race. Yes, the fires and floods of death may whelm or overwhelm.

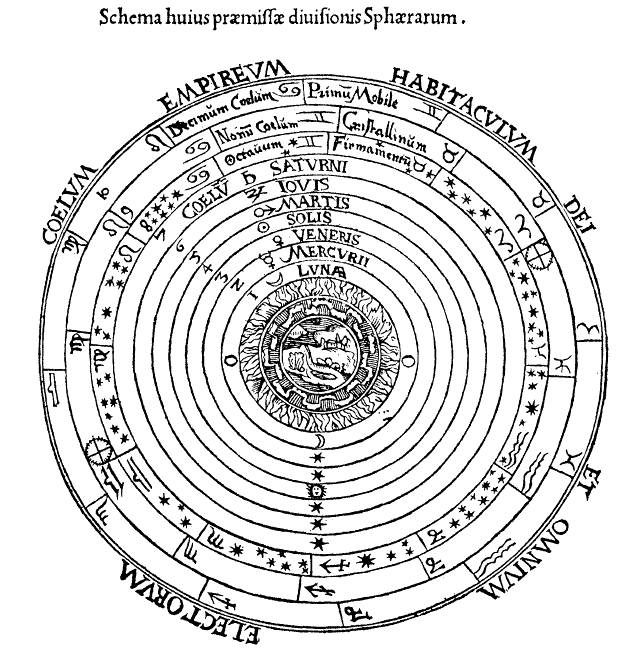

But do not forget that in the hottest fire was a fourth man, and He was like the Son of God. Appearances, like memories, may be deceiving. But you shall know Him when you see Him. He was not like the Son of God: He was. But neither was He, for He sits above Time—that arc which cleaves across Creation—as its Geometer: no, He was not. He is. And in Him, the precarious present tense may be seen for what it truly is: the spinning infinitude of all that is Real, the Primum Mobile, resting tangent to the Empyrean, forever and ever, world without end.

Wow

Really enjoyed this Paul, thank you