The Marriage of Figura

A story about a man who falls.

Written about a decade ago as a stylistic half-joke, half-experiment. But is it a joke? If every sentence is, is any?

Sunshine was melting down through the trees above, the pure oranges and yellows percolating through leaves and clouds alike, littering the roadside with gently jostling shadows, jostling because of the gently flowing breeze, flowing because of a cold front sweeping down from the north. Suburbia was in all its resplendent glory glowing: the smell of hot tar rising in great waves off the freshly surfaced street (with sharp, perfect rectangles of yellow demarcating the crown of the gleaming asphalt), the glint of stainless steel blazing behind the green of the street signs, the streets themselves named with green—with the verdant names of the trees toppled to erect the streets and structures—the hand-painted “Open” signs scattered amongst the sidewalks and storefront windows (for in this district, an ordinance banning neon signs was in place, for neon was thought to cheapen the community’s image), the quiet, restrained roar of luxury cars whose engines never get out of third gear but which yearn for fifth, much less eighth, and the bustle of mothers and wives trundling from shop to shop, like pilgrims moving from shrine to shrine, worshiping for but a moment at each before passing on to the next.

Suburbia was in all its resplendent glory glowing.

Glowing all the brighter, however, was Gaia. If only her crass tenants were not blind to her effervescent beauty! The lively creek, pouring over rock and mud and grass, the white foam appearing like so many flowing crystals, the deep clear blue like a magnificent tapestry being spun out on the loom of Time. The trees flanking the water were adorned like royalty: purples, pinks, yellows, blues, reds, all quietly floating up and down in the ocean of air, every breeze as if a miniature tide.

Not all of the tenants were blind, however: Gaia felt the lusty gaze of one, a man, a man unaccompanied, a man half-beast and half-angel who felt wholly beastly.

He was young, but by his reckoning, an old soul in a young body. His lover had left him, and with her, she had taken his heart’s flesh. All that remained was a stony organ, calcified over by pain and grief unending. He fancied himself deeply romantic, but not at all a Romantic—he had all sorts of most particular niggles with Romanticism—which made him all the more a Romantic, albeit unwittingly (thus making him the worst sort of Romantic). The situation was less that he had a bone to pick with the world and more that he had a whole host of skeletons to pick with the world. But none with Gaia. Her sweet, succulent flourishment was his singular source of vivacity. He lived for her. But when the time came, would he be ready to die for her?

His languid, slouched walking cut a wandering oblique to the bright and boisterous shops. Why not be physically alone if I am existentially alone, or so his reasoning went; and here, his company was solely Gaia. The street signs were weathered, the tree branches thicker, and the automobiles fewer. He liked this street. Here, he found refuge from the encircling ooze of capitalism, the indefatigable commercial forces, forever bearing down on his beautiful hamlet. Here, the mold of mercantilism was supplanted by actual genuine mold emblazoned like patchwork on the rotting houses of the old former days. Here, romance and love intermingled like the coiled kindling of a campfire. Here, passion burned bright and clean.

At one tree in particular, his torpid travel found abrupt pause: a younger tree, adorned in cherry blossoms, each twinkling out in pinks and whites under the shadow of the massive oak farther off the cracked sidewalk, the paving stones cracked up and down and crosswise in great sweeping angles by the swelling roots of the oak. The rain of recent days had brought out the blossoms, like salt does to meat, and pain, wisdom. He stood dazzled as, in his mind’s scintillations, he beheld the blossoms transfigure into Gaia herself in all her feminine mystery and clarity, the form both blurry and sharp, wispy as smoke but smoke which is lit by flames from behind which are lending form and boundary to the flighty shapes.

After an endless expanse of time—whether five minutes or five days he knew not—a passing car wrenched him from the reverie. Gaia sublimed back into the cherry blossoms, the shadows of the oak flew back into relief, the sun burned back to orange from hallowed clean pure white, and the lifelessly blunt reality of a mere Monday afternoon flooded his senses. He turned on his heel and continued on his ruminative way. Yet Gaia would not so casually lose her suitor! His heart sprang forward with a gulping thrill, pinpricks trickling over his skin and into his bones; a sudden slowing of time’s passage, as if the canal locks had been damaged, or a clog down the line were causing a faucet to choke and gurgle; a heady weightlessness, but not one which like the reverie was entirely in his head. He truly was weightless, and the broken stones beneath his feet were spinning toward him—but so slowly! It was a headlong pivot toward disaster, an acceptance of a black widow’s offer of a dance, the climax of the drama when the leading man is smote down by rank injustice, the end of an era, nay, the end of an epic. His death was upon him.

Yet Gaia condescended, and she spared him, and he was crumpled against the stones, blinking at his hands in front of him, and he had caught himself. His ears were ringing, marginally, off in an unattended alley of his mind; a cool dampness was impressed upon his brow; cherry blossoms stuck off his hands like he were a sapling; his knees ground against the solid stone reality. Was this still the reverie? His mind raced, but like his walking had been, to nowhere in particular. But his dampened brow! He must have been concussed. Yes, he had caught himself, but not soon enough, and his forehead had fallen against the oak-warped stone. That was it. Clambering to his feet, a brief romance flickered through his mind: a lovely lively lonely woman, spying his staggering form from her kitchen, rushing out to give him aid, and looking deep in his eyes like only a woman can, and her being enraptured by his old soul, and her helping him to her house, and her hearth… and herself… and then he slips again, landing on his knees, facing the blossoming tree. Tho’ it were a tree no more, again transfigured, the sunlight again a holy albus, the dancing shadows again elided, the day again unlike any which had come before.

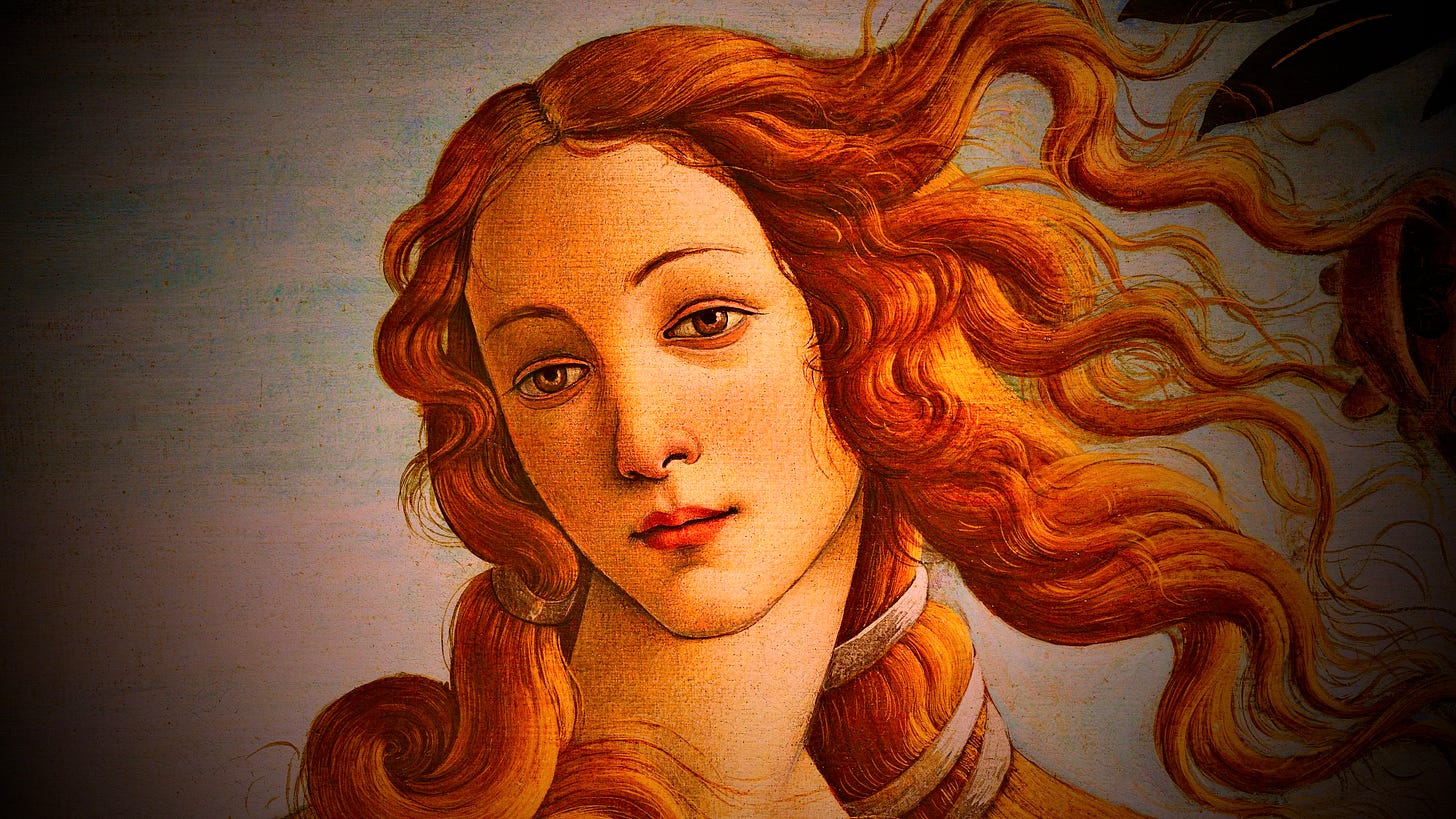

She more resembled now the backlighting fire than the wisps of smoke. Searing anger, a jealous furor, enveloping her shimmering visage. All mystery now gone: her power and might nakedly bared; the blossoms clothed in fiery raiment; the great oak above bending to enshroud him in darkness and expose her to the sheen of Sol; her long flowing hair blazing a sacramental Titian; the depths of his unknown desires plumbed and exposed. She was his love, and his imagined tryst was a blasphemous abomination unto Gaia. Surely this was the end.

As Gaia blazed her most blinding, the rush of awe flooded out of him, and mid-genuflection he looked up to see the stillness of the cherry blossoms, again simply twinkling, simply stars in the delicately undulating galaxy of the oak’s shadow. His forehead was dry; there had been no concussion. Not of the physical sort, at least. His lover had gifted him a concussion of a much greater sort: a concussion of Beauty. Rising to his feet, bewildered, he throws out hopeful glances every which way—perhaps Gaia was still about—perhaps he could yet spy her, see her, be engulfed in her. But she was gone. In the house nearby, he catches the eye of a lovely lively woman, who smiles warmly at him. Only after he has reciprocated does he realize that her husband’s hands had wrapped around her from behind and were now holding her, and she had twirled ’round to complete the embrace, and the smile was never meant for him, and she was not the lonely one, because he was. Was he?

The literally hopeless romantic, the worst sort of Romantic, the sort who denies his own identity: he, even he, had fallen into a Titanic romance. His old soul had found favor with the oldest soul of all, and his young body had been claimed by eternally young blossoms. And so with a sort of hope (although he would never admit to it), he resumed his walking. The strides a little longer, his shoulders a little squarer. He passed from that sacred place, passed the creek with its infinite slight rumblings and whispered wisdoms (for Gaia had now given him ears to hear such things), passed through the pell-mell boisterousness of the marketplace royalty and their loyal subjects, and passed by his past’s outrageous wrenchings and retchings; and by doing so cast his past, his endlessly pretentiously presaging past, at the feet of salvific Gaia.