This New Command I Give You

Love one another...

Music for today:

Welcome, welcome, one and all. Welcome to the inauguration of Bits of Paul. This has been a long time coming. Friends, coworkers, neighbors, going all the way back to high school, have told me that I ought to publish. Well, that day has come. And on this verbal maiden voyage, I think it is fitting to start with the most important thing.

At the back of every discussion of the good society lies this question, What is the object of human life? The enlightened conservative does not believe that the end or aim of life is competition; or success; or enjoyment; or longevity; or power; or possessions. He believes, instead, that the object of life is Love. He knows that the just and ordered society is that in which Love governs us, so far as Love ever can reign in this world of sorrows; and he knows that the anarchical or the tyrannical society is that in which Love lies corrupt. He has learnt that Love is the source of all being, and that Hell itself is ordained by Love. He understands that Death, when we have finished the part that was assigned to us, is the reward of Love. And he apprehends the truth that the greatest happiness ever granted to a man is the privilege of being happy in the hour of his death.

Russell Kirk, Prospects for Conservatives (1989).

So, then. Love. The object of life. What is it? How do we do it?

Much ink has been spilled over love—and thus you think, “And ol’ Paul here has something new and novel to contribute?!” Well, yes, I think I do, in a manner of speaking.

But first, another quotation.

If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence. As it is, the quickest of us walk about well wadded with stupidity.

George Eliot, Middlemarch (1871-1872).

Kirk tells us that the object, or telos, of human life is Love; Eliot tells us that a universal sensitivity to all our fellow men should kill us if we gained it. Let us paint a synthesis of the two.

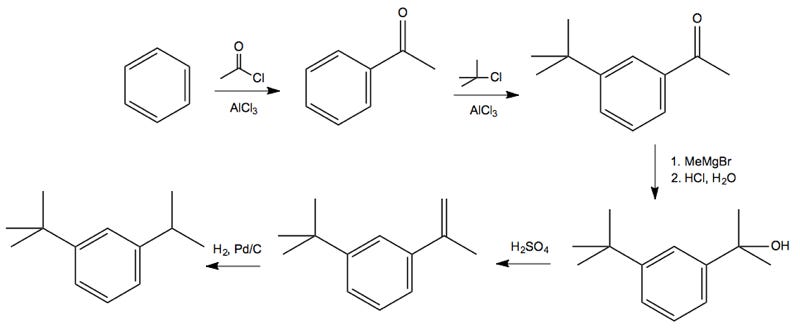

When planning a reaction sequence, the technique of retrosynthesis is often employed by organic chemists. In a retrosynthesis, a precursor compound, or starting reagent(s), is drawn at the top-left; on the bottom (either right or left, space permitting), a target compound, the intended product. As the retro- implies, the reaction sequence—the order of reactions, with accompanying reagents, temperature ranges, and environmental conditions—is worked out backwards. You write and draw out intermediate steps in the reaction sequence, often moving right-to-left, having to budget out space for the various shapes and words necessary. Everything about it is backwards, although when it’s complete, it looks perfectly straightforward and front-, not back-, wards:

To begin, you note strategic disconnects in the target compound. In this case, two such strategic disconnects are on the top-left and -right positions of the benzene ring (the 1- and 3- positions, respectively). You then, working backwards, cleave away the strategic disconnects (or clear the way for unhindered access to them, when necessary), resulting in smaller and smaller molecules which can then be similarly broken up.

Insofar as higher mathematics is described as breaking down a problem over and over again until it becomes a problem you already know how to solve, organic chemistry consists of the same. Indeed, for those readers familiar with calculus, retrosynthetic analysis is remarkably similar to such techniques as integration by parts and trigonometric substitutions. You rarely work forward from a precursor; rather, you begin at the end, and work towards the beginning.

Love, a state of perfect synthesis with God and the world, is the end. But to live in love, we must move backwards. We must, in a sense, live backwards. Here, I shall rely upon Kierkegaard, which I shall not quote at length (on account of time). In Fear and Trembling, he writes that before one can love the world, one must infinitely resign the world and everything therein in exchange for God, for the Infinite. However, after such resignation, God in turn returns to us the possibility of Loving the world.

So, with love as our end, to move backwards (each movement is a strategic disconnect), just before that is a pure, total, complete love for God and nothing else. Moving further backwards, we have the Infinite Resignation. Moving yet further backwards, we have the Faith necessary to make such a resignation.

Faith, then: faith is a submission to, and the understanding of—the standing under—the right ordering of the world. That I, the self, and my relation to the Infinite (which is God), is of higher weight than the whole world. That only in a right ordering of that relation may I hope to properly love and care for the world.

There is a deep, inexorable hierarchy to the world, to Creation. This cannot be evaded or elided. (Though many have tried and continue, evermore, to do so.) In the contemporary West, we are prone to resent, if not shrug off altogether, such hierarchy; we yearn, or think we yearn, for equality. For egalitarianism. For fairness. For the infinitude of potential, of opportunity, of choose-your-own-adventure living.

But we are not meant to have it all, to do it all, to bear it all. We are not God: Father, who has it all; Son, who did it all; Holy Ghost, who bears it all.

We cannot seize possession of the world, enjoy everything in the world, or carry the weight of all the wrong in the world. We are but men, meek images of the Almighty. We are not Atlas.

No, it’s all much less grand than all that. We have our little spheres, bathed in the music of the spheres; we have our gardens of affection, which we are given to tend. For we are not Atlas.

We are called to love our neighbors, not to make the entire Creation our imminent neighbor immediately. If we could contrive such a neighborly explosion, as Eliot wrote, we should die of that roar; and so thank God that, despite all the floundering finaglings of mass media, social media, and every other sort of media, we have not succeeded in making all Creation our neighbor.

This is not to say that a love for all is wrong; indeed, Christ Himself realized that very thing. But Christ is God, and we are not. Let us start with the small spheres, with the little gardens, with our actual real genuine definitional neighbors—you know, those people whose mail sometimes ends up in your mailbox. Remember that to those who are faithful with little, much shall be given.

Every symphony starts as a single measure. That measure, itself a blossomed idea, blossoms into a line; that line, an entire system; systems, pages; pages, movements; movements, a symphony.

I have titled this publication Bits of Paul because, despite being composed of syntheses, it itself is not a realized synthesis. It is just bits of me, little fractionated particles spinning off into the magnificent swirl of human communion. O, the bits certainly do paint a picture, but is it complete? Could it even be? How might we, who haven’t yet faces, see Faces till we have Faces ourselves?

These bits shall spring from poetry, from song, from biochemistry, from history, from theology, from the raving lunacy of The Current Thing(s), from the mundane happenings of my everyday, from the twinkling eyes of giddy children, from the twinkling eyes of giggling elders; these bits shall spring from even some of you, should you write in return.

These bits spring from Love, for Love is the object of all.

Would you be interested in having a conversation with me on my YouTube channel,The Meaning Code? I talk to scientists and philosophers about the intersection between science, faith and art.

Thanks man, God bless